A view of the high Norwegian Arctic while aboard the research vessel Lance (July 2015). Rick Bajornas/UN, CC BY-SA

Today, the world’s oceans are faced with threats at every turn – accelerating climate change, loss of marine biodiversity, and expanding resource extraction, including deep-sea mining, and more. These all come at a time when humanity’s dependence on the ocean for food and job security is higher than ever before.

The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development – known as the UN Ocean Decade – began in 2021 and aims to ensure ocean sustainability into the future. This vision demands collaborative action across sectors, disciplines, nations, communities, and generations. Its success relies on the inclusion of a diverse array of voices that represent current and future ocean leaders. As emerging ocean leaders, early-career ocean professionals will play a key role in designing and executing the inclusive ocean knowledge needed to achieve success.

Since its inception, the UN Ocean Decade has recognised the important role of self-identified early-career professionals working in all fields related to the ocean – not just science – by facilitating the creation of an informal working group (IWG), which has already attracted interest and early-career ocean professionals from around the globe. The working group, of which we are a part, is tasked with creating a strategy for engaging and incorporating younger perspectives and input throughout the UN Ocean Decade.

If our work is successful, inter-generational diversity (and recognition of its importance) will be a central component of discussions around ocean sustainability, even beyond the end of the UN Ocean Decade in 2030. Our goal is to enable transformative change in how ocean science, solutions, and innovations are designed and implemented.

The informal working group is positioned to drive such an inter- and transdisciplinary revolution in how we generate and use actionable ocean knowledge. We and other early-career ocean professionals are already encouraging inclusive and participative approaches for creating innovative and effective ocean solutions.

Members of the ECOP informal working group (L-R Evgeniia Kostianaia, Erin Satterthwaite, Harriet Harden-Davies) meet with Vladimir Ryabinin, IOC Executive Secretary. Alison Clausen/UNESCO

Ocean leaders in action

Recognising that the ocean is facing unprecedented levels of threat due to human activities), members of the working group are engaging in efforts to address the multiple challenges affecting coastal, deep-sea, and open-ocean waters. We are leading new research topics, as well as developing creative initiatives to communicate ocean science and enhance people’s connection to the ocean globally.

Many early-career ocean professionals are working and conducting research on topics related to climate change, including addressing concerns on the increasingly warming and acidifying ocean, and developing climate adaptation strategies. Climate action and adaptation require innovative and proactive approaches that can incorporate diverse environmental, social, and economic factors. Early-career ocean professionals are well-positioned to drive these approaches and our work will be integral to achieving the vision of the UN Ocean Decade.

Early-career ocean professionals are also involved in a wide range of efforts directed toward tackling marine litter, ocean waste dumping, and overfishing, as well as the promotion of ocean sustainability and regional ocean governance.

One specific focus is on areas of the ocean beyond national jurisdiction, a particularly challenge from scientific, enforcement, and governance perspectives. This work addresses topics such as sustainable fisheries management, the designation of marine protected areas, as well as other forms of spatial management. A key goal during the initial years of the UN Ocean Decade will be to develop a legally binding instrument – currently under negotiations under the auspices of the UN – on the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in the high seas. Increasing engagement of early-career ocean professionals in this and other such intergovernmental processes is essential to ensuring that emerging leaders are equipped to implement and expand on these processes.

Other young professionals are conducting critical work on nascent – and potentially high-risk – resource-extraction activities, such as deep-sea mining. Scientific knowledge of the deep sea remains limited, but new developments are emerging in low-cost observation technology, including deep-sea camera systems that can advance research on biodiversity, species distribution and behaviours.

Scientific research and other types of learning, including Indigenous and traditional knowledge, will help us better understand the deep sea and other marine environments – and inform and improve the management and regulation of these crucial ecosystems.

Ocean futures

As more early-career ocean leaders emerge and work together over the course of the UN Ocean Decade, our collective vision and mission must reflect these new voices. Membership of the informal working group is reflected in the present list of co-authors, who come from all regions of the planet.

While we are predominately academics (71%) and government employees (11%), many others bring insights and expertise from civil society, ocean industries, and intergovernmental organisations.

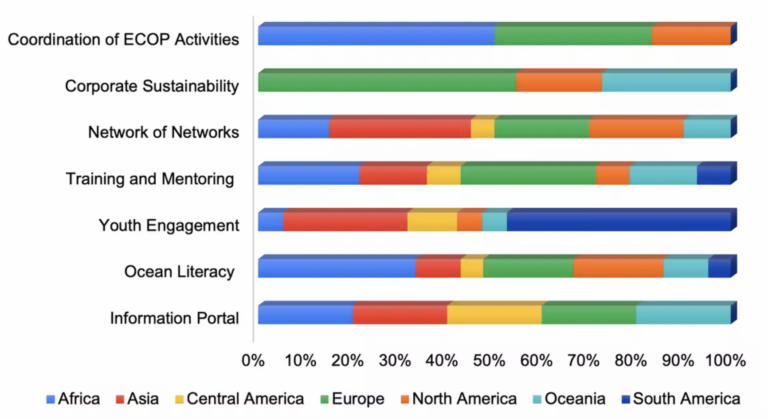

We have self-organised into groups that focus on different topics including corporate sustainability, training and mentoring, youth engagement, and ocean literacy (Fig. 1). Enhanced global ocean literacy across generations and sectors will be key to achieving the vision of the UN Ocean Decade. Early-career ocean professionals are working on diverse research and engagement initiatives to improve community understandings and connection to the ocean at local to regional scales.

International representation across the ECOP sub-working groups.

One important goal is to connect people and communities to the ocean, to inspire them to engage in pro-environmental behaviours and conservation action.

In efforts to achieve the ocean science transformations envisioned, some early-career ocean professionals are reimagining the knowledge-generation process and are creating new opportunities to communicate. For example, collaborations between art and science can enable scientists and communities to better investigate and communicate experiences of the ocean as well as ocean research.

Marine citizen science is another way to engage communities by enabling participants to interact directly with science, and even shape research questions. For example, beach clean-ups are a form of contributory citizen science that engages communities with their local marine environments and also generates data on the impacts of ocean pollution, including animal interactions with debris. The data can then be used to identify the scale and impacts of environmental challenges and inform the development of actionable solutions.

By partnering with youth and community groups, early-career ocean professionals can collect data at larger scales. Here they are seen working with local school students in Tasmania to conduct research on plastic ingestion by local seabirds. Based on the knowledge they gain, some students have even felt empowered to demand government action. Peter Puskic/UNESCO, Author provided

We have much to gain from and contribute to large-scale, international and trans-disciplinary initiatives by providing novel and innovative ideas to ocean questions and challenges.

However, if we are to become ocean leaders who can work to protect valuable institutional and cultural knowledge and promote shared ownership of the actions that affect multiple generations, support is needed at a grassroots level.

Improved and equitable access to resources and infrastructure will be key for mobilizing early-career ocean professionals and in the regions where their ideas and energy are most needed. Only in this way can we empower this and future generations to create innovative and inclusive ocean solutions needed to achieve a sustainable 2030.

Authors

Rachel Kelly

Postdoctoral Research Fellow – Future Ocean and Coastal Infrastructures (FOCI) Consortium, Memorial University Canada & Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania

Rachel Kelly

Postdoctoral Research Fellow – Future Ocean and Coastal Infrastructures (FOCI) Consortium, Memorial University Canada & Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania

Pradeep Arjan Singh

Research Associate (Ocean Governance) at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies in Potsdam, Germany and Doctoral Candidate at the University of Bremen, Germany

Other Contributors

Riaan Cedras, Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape, South Africa; Alessia Dinoi, Centre for Ecological Genomics and Wildlife Conservation, Department of Zoology, University of Johannesburg, South Africa; Jonatha Giddens, National Geographic Society’s Exploration Technology Lab, United States; Alfredo Giron-Nava, Stanford Center for Ocean Solutions, Stanford, CA, United States; Claire Mason, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia; Guillermo Ortuño Crespo, Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University, Sweden; Peter S. Puskic, Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia.